For over thirty years, Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman has been counted as a definitive classic of the comic book medium, expanding the storytelling boundaries of exactly what comics can do. For much of its run, The Sandman was published under DC’s former mature-readers imprint, Vertigo. One thing Vertigo was known for, apart from its subject matter, was that the titles it published typically had little to do with the DC Universe, where DC’s superhero comics share their world.

Because of these factors, it’s often assumed that the Sandman comic has no DC Universe connection. But from the very first issue, Gaiman draws on lore from DC history as much as the other mythologies and cultural traditions from our own world to shape the Dreaming. But this is the “DC House of List-ery,” so let’s look at some examples. Here are six different ways the world of The Sandman crosses into the DC Universe.

Of Sandmen Past

Of Sandmen Past

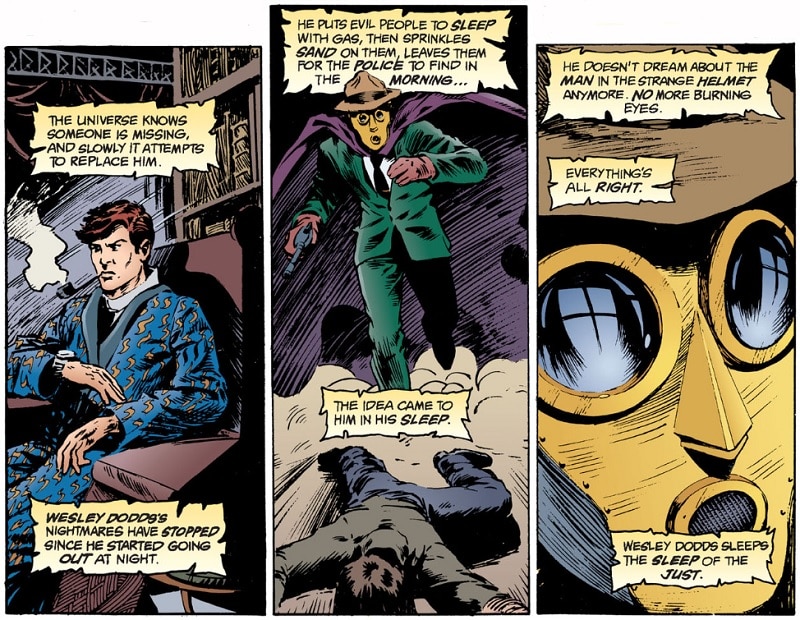

Dream of the Endless is not DC’s first Sandman. Or even the second, or third. Those prior bearers of the title, more akin to traditional superheroes in their own right, are each addressed through Gaiman’s narrative in their own way. The original Sandman of the Golden Age, the gas mask-wearing Wesley Dodds, appears in Sandman’s very first issue. At a time when Dream is imprisoned, we take a moment to check in on Wesley as a man inspired through his dreams to fight injustice. Though it had never really been a feature of his character before Gaiman introduced it, from here on out, one of Dodds’ definitive traits would be his prophetic dreams which grant him a wider perspective on the universe.

In 1974, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon created their own reimagining of Sandman, a man named Garrett Sanford. After an accident traps Sanford in the “Dream Dimension,” the collective subconscious realm where all dreams take place, Sanford resolves to become his new home’s resident superhero. As Sandman, Sanford patrolled the dream world with the help of dream creatures Brute and Glob, and a young dreamer named Jed Paulsen.

In Infinity Inc. #50, we learn that Sanford had committed suicide as a means of granting himself release from the Dream Dimension. Brute and Glob replaced Sanford in his duties with recently deceased Infinity Inc. member Hector Hall, who is allowed to enter the Dream Dimension with his living wife and fellow Infinitor, Lyta Hall. At the time they entered the Dream Dimension, Lyta was pregnant with Hector’s child.

As it turns out, more than any other event, this pregnancy is the most relevant story detail from the DC Universe to the narrative of The Sandman. The true nature of Garrett Sanford and Hector Hall’s arrangement with Brute and Glob is revealed in The Sandman: A Doll’s House. Lyta’s pregnancy would resolve in the birth of Daniel Hall, a human child born in the Dreaming. Because of this, Dream claims Daniel as his own. Lyta is not on board.

The Horror Hosts

The Horror Hosts

In the second issue of The Sandman, we have our first visit to the Dreaming—the realm where Dream holds court over the dreams of all living, thinking creatures. As it happens, fans of DC’s Bronze Age horror titles will recognize many familiar faces among its subjects.

The quarrelsome Cain, Abel and Gregory the Gargoyle: hosts of the long-running twin titles of The House of Mystery and The House of Secrets. The reclusive, cave-dwelling Eve: host of Weird Mystery Tales and Secrets of Sinister House. The Fashion Thing was once the Mad Mod Witch, host of The Unexpected. In a much-upgraded role, Lucien the Librarian was formerly host of the short-lived Tales of Ghost Castle. The three fates with whom Dream consults are Mildred, Mordred and Cynthia, hosts of The Witching Hour. Even Dream’s eldest brother, Destiny, originated as a host of Weird Mystery Tales in 1972. Through the Dreaming, The Sandman connects the previously disjointed classic horror titles of the DC Universe, building a strange and appropriately sinister community between them.

A Spiritual Swamp Thing Sequel

A Spiritual Swamp Thing Sequel

Like so many comic luminaries, Neil Gaiman owes his success in the field to a mentor who showed him the ropes at the start of his career. In Neil’s case, that mentor was none other than Alan Moore, who showed Gaiman the art of turning a story into a comic book script from soup to nuts. If you’ve read Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, the storytelling style of The Sandman may feel familiar to you. That’s no coincidence. Swamp Thing was Gaiman’s bible in learning how to craft a story for comics.

With that, you can find connections to Moore’s Swamp Thing throughout the Sandman saga. Gaiman’s descriptions of Hell in Preludes and Nocturnes and Season of Mists are taken right from Swamp Thing’s own journey through the underworld in Swamp Thing #50. An early appearance by John Constantine, and later his ancestor Johanna Constantine, are both tributes to Moore’s own nasty piece of work. And then there’s Matthew the Raven, Dream’s constant companion, who in a former life was Swamp Thing’s friend and romantic rival, government agent Matt Cable. The very blueprints for the concept of the Dreaming itself, in fact, are directly taken from Moore’s Swamp Thing #33, when Abby Arcane encounters Cain and Abel as she visits the House of Secrets in her sleep. It’s no exaggeration to say that without Swamp Thing, there would be no Sandman.

The Dreamstone

The Dreamstone

Much of the first volume of Sandman, which we’ll see covered in this first season of the Netflix series, is concerned with Dream tracking down his Dreamstone, a ruby imbued with an enormous portion of his power. As Dream would learn, his Dreamstone had been co-opted years ago by a foe of the Justice League of America: the skeletal Doctor Destiny, whose “materioptikon” (in fact, the dreamstone) allowed him to manipulate the dreams of his enemies.

In The Sandman, we find John Dee in Arkham Asylum, enduring the soliloquies of the Scarecrow before he makes his escape and unleashes the full power of his ruby on the world. In hunting down his Dreamstone, Dream encounters the late ’80s contemporary Justice League. Dream grants peaceful rest to Mister Miracle, who suffers still from nightmares of Apokolips, and appears to Martian Manhunter in an aspect as an ancient Martian god of dreams—demonstrating to us that to each culture throughout the cosmos, Dream takes a different form.

The Forgotten Elements

The Forgotten Elements

As The Sandman finds its footing, references to the DC Universe fade further into the background, allowing the book space to explore its own established mythology. But every so often, a guest star will continue to poke their head in to remind you just where this is all taking place.

In The Sandman #20, we learn the sad fate of Element Girl, former partner of Metamorpho, whose existence in obscurity is a waking nightmare. The Sandman #54 features a retelling of the Prez: Teen President series of the 1970s, inspired by the life and legacy of John F. Kennedy. When Lyta returns to the waking world, her government liaison is Eric Needham, former Gotham vigilante Black Spider. Sandman’s fourth volume, Season of Mists, features an array of gods and cosmic authorities of all kinds vying for Dream’s favor, including Doctor Fate’s Lords of Chaos and Order, and a Norse collective with a bottled instance of Ragnarok forever being fought by the Justice Society of America (as seen in Roy Thomas’s 1986 JSA finale The Last Days of the Justice Society of America).

Perhaps the most interesting of all The Sandman’s cameos is an appearance late in the run by Batman and Superman in the Dreaming—where we learn that the ’50s and ’60s Superman and Batman TV shows all actually took place within the dreams of their respective heroes. (Martian Manhunter, for his part, claims he’s never had dreams like those…but we can only imagine that these days, when J’onn sleeps, he dreams of Supergirl.)

Super-Powered Sessions

Super-Powered Sessions

Sandman ended its original run in 1993, but Dream and his siblings have continued to influence the DC Universe ever since. Follow-ups such as Endless Nights and The Sandman: Overture revisit Sandman’s place in DC’s cosmology in ways so interesting that it would be a shame to spoil them here. (If you get the chance, ask Dream’s sister Despair some time about the destruction of Krypton.)

Apart from Neil’s own work, other writers have occasionally gotten the opportunity to take the Endless for a spin. Dream plays a significant role in JLA #22-23, “Perchance to Dream,” where the Justice League battles Starro on two fronts of reality and the Dreaming. Kevin Smith’s Green Arrow features the same occult order that ensnares Dream in The Sandman’s first issue. Geoff Johns’ JSA offers the return of Hector and Lyta Hall, picking up right where The Sandman left them. In Mark Waid’s The Brave and the Bold, Supergirl is charged with finding the lost Book of Destiny. In the aftermath of Blackest Night, Lex Luthor’s quest to harness the power of the Black Ring brings him face to face with Dream’s sister, Death. And most recently, Dream appeared to Batman in Dark Nights: Metal to enlist his aid in a crisis which threatened all worlds both real and imagined.

“The Sandman is pretty much its own thing,” eh?

As you can see, the reality isn’t so simple. Yes, Morpheus and his world largely exist independently of the greater DCU, but certainly not removed from it. Sandman is a work all its own, and yet Sandman is a work of DC. And as DC’s multiverse continues to expand, it’s only natural that occasionally, its denizens will bump into the realm of the Endless. After all, even heroes dream. And what are dreams—and comic books—but stories.

Perhaps the “D” in DCU actually stands for Dream?

DC House of List-ery runs every Thursday here on DC.com.

The Sandman, starring Tom Sturridge as Morpheus, debuts on Netflix this Friday, August 5th. For more dreams, fables and recollections, visit our official Sandman TV page.

Alex Jaffe is the author of our monthly "Ask the Question" column and writes about TV, movies, comics and superhero history for DCComics.com. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexJaffe and find him in the DC Community as HubCityQuestion.