It's that very magical time of the year once again. No, not Christmas... It's Batman Day, when we celebrate the death of two rich philanthropists and the massive trauma that it bestowed upon their young son, Bruce Wayne! In the spirit of this joyous holiday, I thought I'd look back upon one of the most spirited and ecstatic versions of Bat-Lore and the huge impact that it had on the Batman comics that ran alongside and followed it. I am, of course, talking about the classic 1966 television show Batman, a series which introduced realms of fans to the Caped Crusader, his ward Dick Grayson and his ridiculous rogues gallery!

The iconic camp of Batman '66 has reached cult status amongst Bat-Fans, and though it's often seen as a charming, if not dated, time capsule of a different era, it was actually a radical and unexpected success that for many viewers became their first foray into Bat-Fandom. Not only did the show widely introduce audiences to the crimefighting capers of Batman and Robin, but due to its massive audience, DC had to adapt their output to keep up with or beat their televised counterparts.

After the implementation of the Comics Code Authority, Selina Kyle A.K.A. Catwoman disappeared from the pages of Batman comics for twelve years. Though an official reason was never given, fans and historians have always thought it was in response to a certain part of the Comics Code that stated criminals could not be glamorized or celebrated. As a regular antihero, sometime love interest, and constant jewel thief, Catwoman was never clearly defined and that made her a prime target for the stringent code. But when ABC decided to use her in their roster of recurring villains, it wasn't too long before Catwoman made her way back onto the page.

Originally brought to life by Julie Newmar in episode 19 of Batman, "The Purr-Fect Crime," by the summer of 1966, Catwoman had also been portrayed by Lee Meriwether in the iconic movie adaptation of the show, becoming a huge fan favorite. So it's no surprise that months later, Selina Kyle also returned to the comic books for the first time since 1954 in SUPERMAN’S GIRLFRIEND, LOIS LANE #70. Catwoman would later be portrayed on the Batman TV series in perhaps her most iconic version by Eartha Kitt, who would play Catwoman until the show ended in 1968.

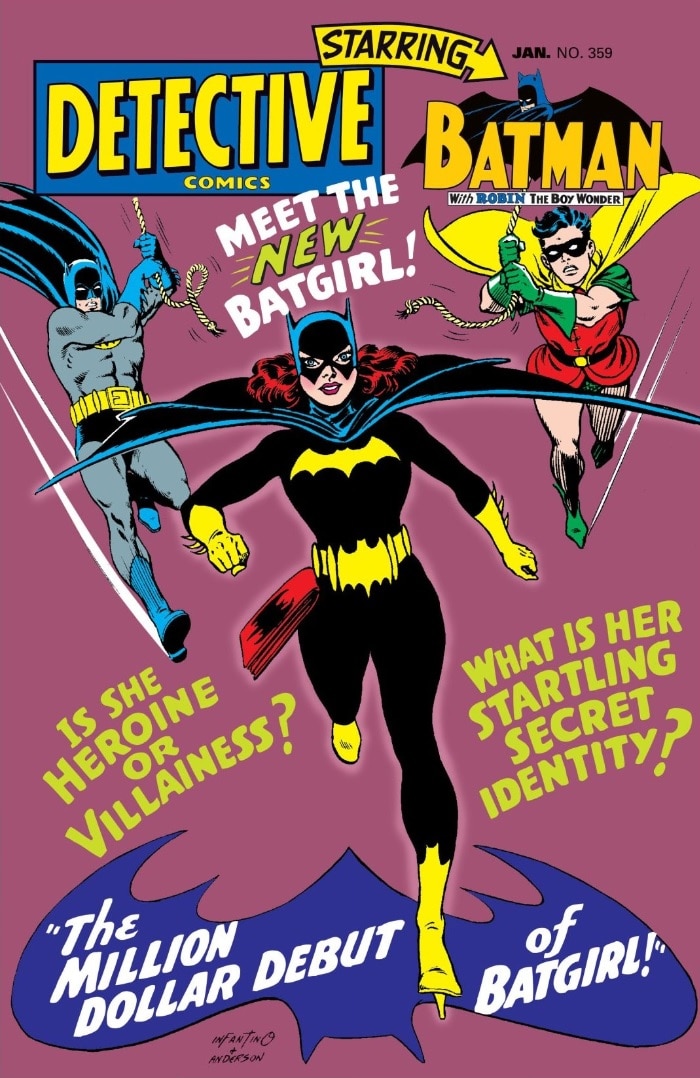

Another famous female character brought into the comics due to Batman '66 was Batgirl. Though a "Bat-Girl" appeared in the comics as Betty Kane for a few issues in the early '60s, Batgirl as we know her wouldn't be introduced in the pages of Detective Comics until 1967. With the popularity of the Batman show plateauing, producer William Dozier decided that he wanted to appeal to the yet-untapped potential young female audience of the show. So Dozier reached out to DC to ask them if they could come up with some new female characters for the show.

Artist and future Editor-in-Chief of DC, Carmine Infantino, heard the call and alongside editor Julius Schwartz designed some femme fatales who could potentially star in the third season of Batman. One of those characters was a new Batgirl.

Barbara Gordon was a doctor of library sciences who fought crime as Batgirl, not because of trauma but because of civic responsibility. Babs debuted in DETECTIVE COMICS #359, seven months before she showed up on the first episode of the show’s third season, though she likely wouldn't have appeared in comics at all if it wasn't for the Batman TV show.

The final and probably most impactful legacy of the show was, ironically, the long-lasting aversion to the campy, colorful and kind Batman that it portrayed. After the series ended in 1968, Schwartz was eager to keep the Dark Knight away from the bright and silly reputation he'd earned during his two-and-a-half-year tenure on television. According to Billion Dollar Batman by Bruce Scivally, Schwartz decided that the Caped Crusader should move back towards his dark roots, the ones introduced by Bill Finger and Bob Kane in his original stories. Enlisting the talents of Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams, the comics took a more adult turn, with even the costume leaning heavily into its noirish origins.

If you've read a main-title Batman comic book over the past fifty years, you know that they never really returned to the cheery campiness of the '66 show. And it wasn't just the comics that were affected, as two decades later Tim Burton would make his seminal film Batman, portraying Gotham's guardian as a serious hero with dangerous foes. That 1989 iteration, combined with the lasting success of THE KILLING JOKE and THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, meant that Batman would forevermore be known as the darkest of knights.

Rosie Knight writes about Young Adult comics and the DC Universe in general for DCComics.com. Be sure to follow her on Twitter at @RosieMarx.